Phase 1: Stability

Once Phase 0 is implemented successfully, in principle and with all countries committed in good faith we will have measures in place that provide defense in depth to prevent the development of artificial superintelligence for the next 20 years.

With safety measures in place and the cautious prospect of two decades to mount our response, the next challenge arises from the potential instability of this system. While universal compliance with Phase 0 measures would be ideal, it is unrealistic to expect perfect adherence.

Systems naturally decay and fall apart unless they are actively maintained. Moreover, individually minor attempts to circumvent the system can compound over time, potentially undermining the entire framework.

We should anticipate various actors, including individuals, corporations, and governments, to put pressure on the system of Phase 0 measures by either trying to circumvent them, interpreting them in a more relaxed fashion, or otherwise launching projects that might violate some of the measures. Over time, these individually small pressures will add up and test the resilience of the system.

To maintain safety measures for the required two decades and beyond, it is necessary to establish institutions and incentives that ensure the system remains stable.

Therefore, the Goal of Phase 1 is to Ensure Stability: Build an International AI Oversight System that Does Not Collapse Over Time.

Conditions

To achieve Stability, certain conditions must be met.

Non-proliferation

International structure

Credible and verifiable mutual guarantees

Benefits from cooperation

Non-proliferation

This condition is necessary due to the fundamental issue of repeated risk problems inherent in proliferation. Even if the probability of a catastrophic event from any single AI development effort is low, the aggregate risk becomes substantially higher as the number of independent actors developing advanced AI increases. Each new party engaging in AI development introduces another chance for accidents, misuse, or unintended consequences. This multiplicative effect on risk is particularly concerning given the potentially existential nature of advanced AI mishaps. By limiting proliferation, we dramatically reduce the number of opportunities for something to go wrong, thereby keeping the aggregate risk at a more manageable level. Non-proliferation is thus crucial not just for geopolitical stability, but as a fundamental risk mitigation strategy in the face of technologies with low-probability, high-impact failure modes.

International structure

The development of advanced AI science and technology must be an international endeavor to succeed. Unilateral development by a single country could endanger global security and trigger reactive development or intervention from other nations. The only stable equilibrium is one where a coalition of countries jointly develops the technology with mutual guarantees.

Credible and verifiable mutual guarantees

For actors to work towards this goal in a stable and durable manner, all key parties must be bound by certain conditions and able to verify others' compliance. Defections must be credibly and preemptively discouraged, with all actors precommitting to jointly preventing and punishing non-compliance. Systems must be in place to verify compliance and quickly identify defections, whether accidental or intentional.

Benefits from cooperation

Alongside credible deterrence, the stability of the system requires that participation be beneficial for all parties. While the primary benefit is the continued survival of the human species, the system should provide additional incentives to discourage defection and encourage participation. These benefits will act as initial incentives to expand the coalition of actors establishing this system.

Summary

Goal: Stability: Build an International System that Does Not Collapse Over Time.

1. International AI Safety Commission (IASC)

Objective

Establish a commission to set the rules governing global AI development and oversee GUARD.

This policy fulfills the condition of non-proliferation, international structure, credible and verifiable mutual guarantees.

Overview

Through the signing of the AI treaty a new international authority should be created to monitor compliance with the treaty, promote AI safety research, and facilitate cooperation between signatories. This institution, which we call IASC, is necessary for providing oversight and ensuring that AI research remains under control. IASC and its employees will have similar diplomatic protections and status to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). This institution should be the central rule setting body for AI development, with a number of powers and responsibilities.

The core roles of IASC is providing oversight for GUARD and lowering the globally applied compute thresholds in the Multi-Threshold System over time to account for algorithmic improvements, in order to hold AI capabilities at estimated safe levels.

IASC will monitor AI research and development, and undertake assessments on the risk of AI advancements.

In addition, IASC will act as the secretariat and depositary to the treaty, and will have the jurisdiction to monitor treaty compliance.

This will include conducting inspections and audits of licensed facilities under the jurisdiction of signatories, analyzing data it collects via its monitoring systems, as well as analyzing data provided to it by third parties (e.g., nation-states' intelligence agencies).

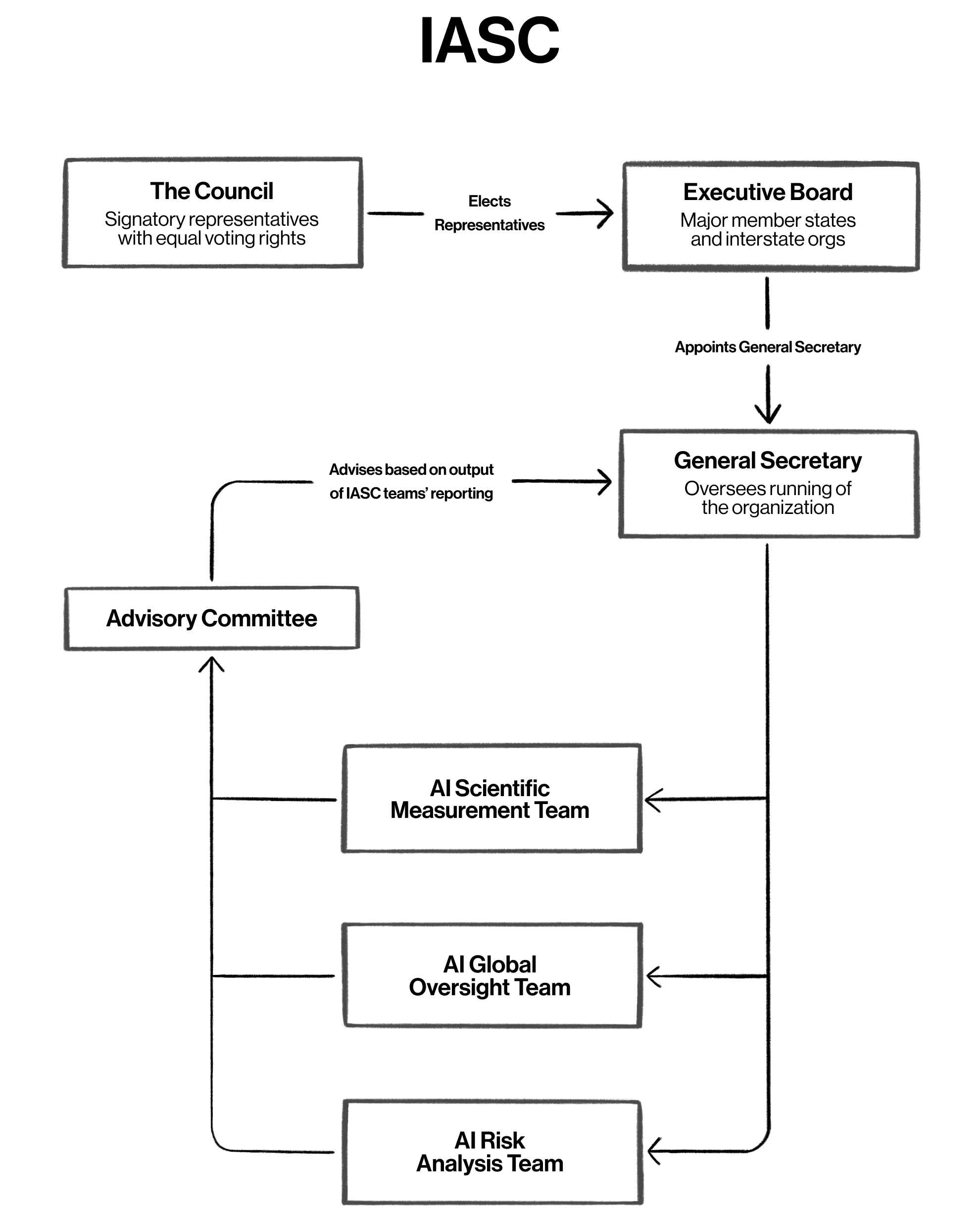

In order to ensure good governance of IASC, a representative chamber known as the Council should be established, along with an Executive Board, and a position of a General Secretary of IASC.

Rationale

In order to have a comprehensive international regulatory framework that ensures continued AI development is conducted in a manner that does not pose unacceptably high risks to humanity, it is necessary to reach international agreement both on rules, but also how they are enforced.

Furthermore, given that such an endeavor will require the cooperation of competing powers, it is necessary to establish clear trust-building mechanisms in terms of inspection, monitoring, and verification procedures.

In achieving this, the risk of defection is mitigated by both reducing the incentives to defect, and mitigating the impact of doing so. Incentives to defect are reduced by creating an expectation that activities in breach of the treaty will be detected. The impact of defection is mitigated by early detection of activities in breach of the treaty, allowing for a response that is able to deter or prevent continued breaches.

IASC Organizational Structure

In order to ensure good governance of IASC, a representative chamber known as the Council should be established, along with an Executive Board, and a position of a General Secretary of IASC.

The Council would consist of a representative from each member state of the treaty framework, and will meet at least once per year to agree countries’ contributions and budget. To ensure sufficient continued operation and capacity of IASC, each signatory country of the AI treaty must contribute an agreed sum annually to IASC.

The Executive Board, analogous to the UN Security Council, would consist of representatives of major member states and supranational organizations, which would all be permanent members with vetoes on decisions taken by the Executive Board, as well as non-permanent representatives elected by a two-thirds majority of the Council.

The General Secretary of IASC should be appointed by a three-fourths majority of the Executive Board, and would have a number of important duties, including most crucially deciding on lowering the compute thresholds. The General Secretary formally makes the decision to lower the compute limits established in the Multi-Threshold System, on the advice of the Advisory Committee, following a report of the AI Scientific Measurement Team.

For a more detailed look at the organizational structure of IASC, outlining its various departments and decision procedures, including the Advisory Committee and the AI Scientific Measurement team, see the annexes.

1.1 Multi-Threshold System

Essential to the functioning of a stable international regulatory system is the Multi-Threshold System established in Phase 0. In this system, AI models would only be permitted to be trained within certain compute limits, and with restrictions on the computing power of data centers used to train them.

Implementation and enforcement

One of the core roles of IASC is in lowering the compute thresholds established in the Multi-Threshold System over time to account for algorithmic improvements which mean that more capable, and more dangerous, models can be developed with a fixed amount of training compute. The objective here is to map the compute threshold proxies onto fixed capabilities levels, in order to keep AI development within estimated safe bounds.

The General Secretary of IASC formally makes the decision to lower compute thresholds, on the advice of the Advisory Committee, and following a report of the AI Scientific Measurement Team.

Following such a decision by the General Secretary, GUARD and national regulators would be legally obliged to implement it and ensure that AI models are not trained in breach of the updated thresholds.

Note: In each limit regime, the largest permitted legal training runs could be run as quickly as within 12 days. For more information, see annex 2.

* We can use the relationship: Cumulative training compute [FLOP] = Computing power [FLOP/s] * Time [s]. By controlling the amount of computing power that models can be trained with, we can manage the minimum amount of time that it takes to train a model with a particular amount of computation. Our aim in doing this is to control breakout times for licensed or unlicensed entities engaged in illegal training runs to develop models with potentially dangerous capabilities – providing time for authorities and other relevant parties to intervene on such a training run.

1.2 Framework for Information Collection and Intelligence Sharing

Within IASC there should be a clear framework for how the organization collects information from countries about their AI development and how intelligence is shared between countries and with IASC. We call this the Framework for Information Collection and Intelligence Sharing. Overall, our approach is inspired by the IAEA’s approach to monitoring nuclear capabilities. However, this approach must be tailored since compute resources are nearly-ubiquitous in everyday life and computer chips must still be deployed broadly for other everyday purposes.

Our proposed framework has five parts:

IASC’s development and execution of inspection and monitoring to proactively analyze and assess global AI development;

IASC’s development (both internally and in partnership with third parties) of verification and monitoring capabilities that can provide general monitoring of major concentrations of compute;

IASC’s analysis and ongoing audit of global supply chains relating to AI development;

IASC’s and GUARD’s system for providing guidance to nation-states implementing the treaty (and their intelligence services) on things to proactively monitor;

The information-sharing mechanism whereby signatories to the AI Treaty (and their constituent regulators, AI safety/research institutes, law enforcement and security services, etc.) can share information on AI to IASC and with each other.

Implementation and enforcement

Inspection and Monitoring

First, IASC should develop an overall inspection and monitoring plan and process. In accordance with specific commitments in the AI Treaty, countries (and the companies, nonprofits, government institutions, etc. residing within them) should be required to submit to regular inspections by IASC staff. These inspections should generate reasonable confidence that the countries party to the treaty, and the entities within them, are abiding by each of the requirements of the treaty. Inspections may be conducted physically in-person (e.g., to verify that a given data center has or lacks advanced chips) or virtually (e.g., remote access to compute, storage, logs, etc.) depending on the requirements of that particular inspection.

As part of the initiation of the treaty, countries should be required to engage in one-time “displays” of their existing capabilities to confirm they are accurate. For example, if the US government asserts that US Department of Energy supercomputers have a certain amount of compute capabilities based on having specific chips, they should be required to do a one-time demonstration of that facility.

Verification mechanisms

Second, IASC should begin long-term research and development efforts to identify longer-term needs to maintain and enhance their inspections program via verification mechanisms. At scale, this will require tamper-resistant verification mechanisms throughout the hardware and software stack. Mechanisms could be developed by IASC, but likely will be more robust if they are developed through a process that also incorporates outside input and testing, similar to the US NIST cipher competitions for general-public and government cryptographic use. To be practicable, these mechanisms would need to be capable of reporting signals of dangerous use of large amounts of compute without generally violating the underlying privacy of compute users. For instance, “reporting dashboard enablers” that help track exceptionally large amounts of compute usage by customers over a given threshold would meet this criteria, but backdoors into every processor would not.

Supply chain audits and controls

Third, IASC should be able to conduct supply-chain tracing and audit relevant export control, KYC, etc. processes to ensure that they are properly applied. These steps are necessary to ensure that even if a non-signatory or a treaty-breaking signatory state runs a hidden, air-gapped program it can be detected.

Detect and advise on signatures of risk

Fourth, IASC should provide the security services of signatories advice on what risks to watch out for, both in terms of technical signatures (e.g., particular patterns of network activity or cloud compute usage) and other indicators of concern (e.g., sharing information on non-state groups that are identified through inspections and monitoring as building potentially hazardous AI). These could enable multilateral efforts to address and mitigate AI risks through mechanisms such as sanctions or prosecutions.

Of course, intelligence tips from IASC pose their own risks, as they could also enhance signatory countries' ability to evade oversight and/or to grow their own capabilities, and will have to be carefully controlled through a disclosure process.

Finally, IASC should provide a framework for information-sharing between countries that are party to the treaty, so that they will be able to share intelligence and information, and cooperate with IASC to identify, monitor, deter, and prevent activities by state or non-state actors prohibited by the treaty.

2. Global Unit for AI Research and Development (GUARD)

Objective

Pool resources, expertise, and knowledge in a grand-scale collaborative AI safety research effort, with the primary goal of minimizing catastrophic and extinction AI risk.

Mitigate racing dynamics, both between corporate AI developers and between nations, by only allowing one organization to work on the true frontier. The lab, subject to its own Upper Compute Limit on the models it can train, develops models in order to meet the priorities of each country that signs the treaty, and to be beneficial to humanity.

Safely develop, explore, leverage, and provide benefits of AI to humanity, enabling the AI systems developed by GUARD to be accessed by 3rd parties for innovative new use cases in accordance with the multi-threshold system.

This policy fulfills the conditions of non-proliferation, international structure, credible and verifiable mutual guarantees, benefits from cooperation.

This policy supports development of safe AI research that enables all of the underlying safety conditions we are trying to achieve through its research, as well as providing supervision of the most-risky AI research such that it is less likely to violate those safety conditions.

Overview

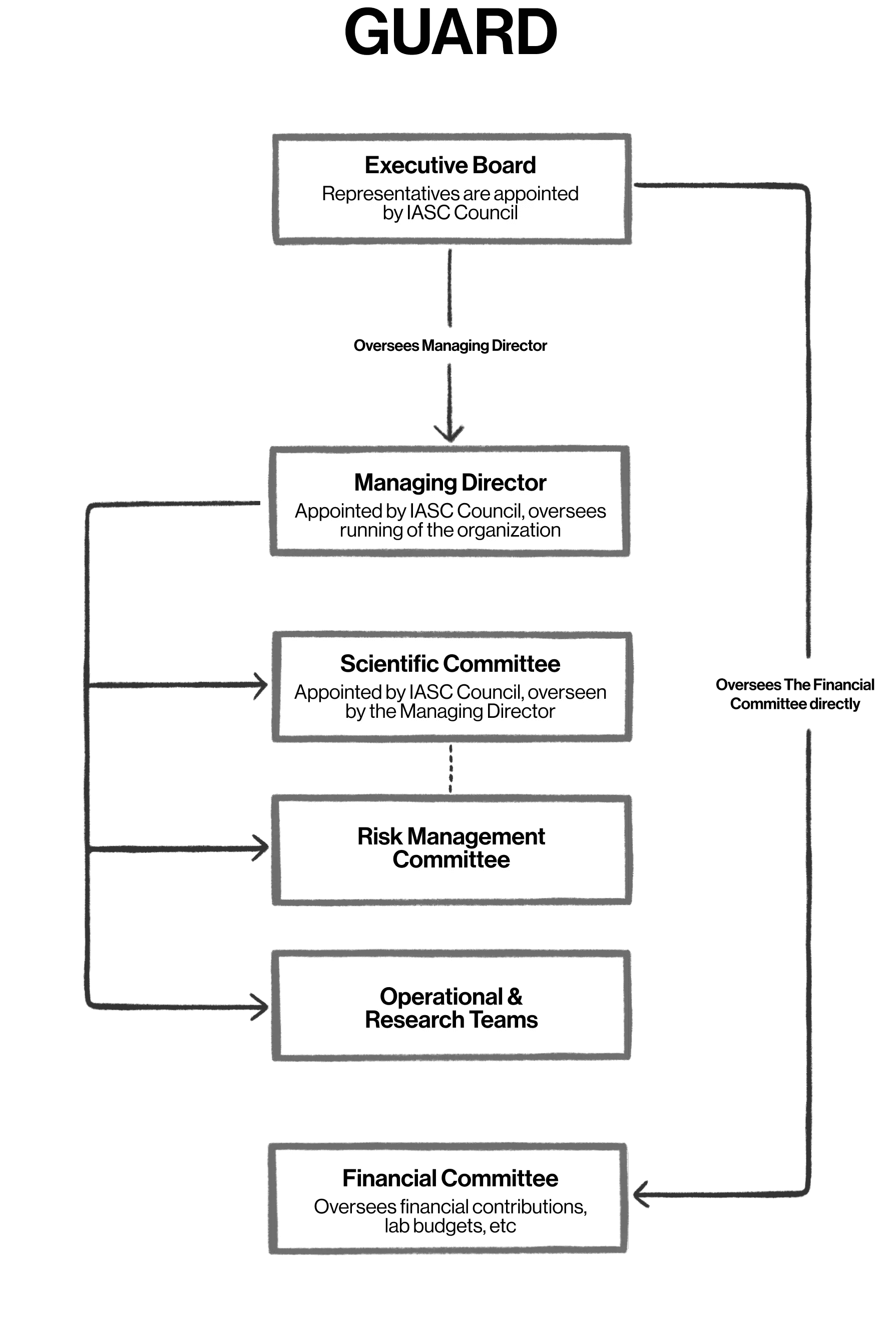

Countries should collectively create an AI research institution, which we call here the Global Unit for AI Research and Development (GUARD). This institution should be governed by IASC to ensure that it properly prioritizes safety throughout its research. Any AI it develops should be bounded, controllable, and corrigible, even if that requires meaningful trade-offs in current or future capabilities.

Rationale

The system is needed to remove the incentives for countries to race to produce unsafe, artificial superintelligence. Without a collaborative, multilateral effort, countries may see AI as an all-or-nothing prize that goes to the first country to develop it, and cut every safety corner they can to build it as quickly as possible; countries that stand no real chance of developing AI in the near future might even engage in cross-domain deterrence and threaten AI-developing countries with acts of war to attempt to deter its development. Through GUARD, we defuse those competitive tensions and their accompanying risks.

However, this poses a problem in turn: any multilateral system runs the risk of bad actors, including nation-states and powerful non-state actors, refusing to participate in the system. A bad actor that seeks to establish their own breakaway AI superintelligence program, either out of a misguided belief that they can benefit from doing so or from a belief that a nascent superintelligence is a “doomsday” threat that could be used to coerce other nations, may ultimately succeed given enough time, resources, and luck. By establishing GUARD, we reduce the incentives for bad actors to break away from the international system as they can benefit from GUARD’s spinoff developments far sooner and with far lower risk than their breakaway program. In addition, rogue actors will be less likely to succeed as the world’s best AI talent will already be employed in a collaborative, multilateral environment instead of a breakaway black project.

Mechanism

Through this lab, Treaty signatories will be able to make progress on AI innovation safely, and engage in higher-risk research in a research community that draws from the best of existing safety research talent, and shares those insights instead of keeping them inside corporate silos. As this research bears fruit to create safe and beneficial AI systems, GUARD will provide access to them to Treaty members; this benefit will encourage countries to join the AI Treaty and GUARD system.

Implementation and enforcement

GUARD will pool resources, expertise, and knowledge in a grand-scale collaborative AI safety research effort, with the primary goal of minimizing catastrophic and extinction AI risk. This will centralize development of the most-advanced allowed AI systems within a single internationalized lab, as part of the internationally-set multi-threshold system (see ‘AI Treaty’ section), where the internationalized lab has its own higher limit than any other entity globally. The internationalized lab will meet or exceed the standards we would also propose for implementation at the national level’s licensing regime and should develop models in order to meet the priorities of each signatory to the AI Treaty and to the benefit of humanity generally.

This access could be provided either as non-AI-model outputs (e.g., a dataset of medical insights to enable new drug discovery) or via verified output33 API access to GUARD’s AI models through a network of lab-operated computing clusters around the world. In practice this will mean that GUARD should share the results of its work, breakthroughs, and best practices unless doing so would pose a hazard, but not release underlying models until the state of the art has advanced to be able to know that it is doing so in a controlled and safe fashion.

The Lab would be supervised by the International AI Safety Commission and should be proactively designed to incorporate lessons learned from existing research institutions; in particular, its institutional design should minimize the risk of internal institutional capture by researchers who willfully cut corners on safety.

The Lab should be run by an Executive Board, informed by expert Advisory Committees (to whom the Executive Board could delegate some day-to-day decisions). The GUARD Lab would be subject to oversight from IASC and in particular, IASC could veto the appointment, order the removal, or order the reassignment to a less-sensitive project of any senior official within GUARD (including the Executive Director; the chair of any Committee or other major research team; any immediate subordinate reporting directly to one of the previously mentioned persons). See Annex 1 for a proposed breakdown of the institutions’ structure.

GUARD would be required to operate under very high security standards, comparable with those who work in other high-risk industries, such as aviation, virological research, nuclear technology research at national labs, or national security agencies. However, these standards will have to be tailored to the context of AI lab work; for example, some work might require operating in a network- and signal-isolated environment similar to an intelligence community Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility (SCIF), but other work might properly require ongoing internet connectivity (e.g., training a model to better forecast extreme weather events based on real-time weather data).

3. International AI Tribunal (IAT)

Objective

Create an independent judicial arm for IASC, with the sole purpose of resolving conflicts, breaches, and differing interpretations on issues relating to the application and compliance with the AI Treaty.

This policy fulfills the conditions of international structure, credible and verifiable mutual guarantees.

Overview

The International AI Tribunal (IAT) should serve as an independent judicial arm of IASC, with the sole purpose of resolving conflicts, breaches, and differing interpretations on issues relating to the application of and compliance with the AI Treaty.

The IAT will work to swiftly adjudicate disputes arising within the AI Treaty framework and interpret the treaty’s provisions.

Rationale

As with many other international agreements, it is all-but-necessary to have an adjudicatory body to resolve disputes between parties to the treaty. Without such an adjudicatory body, the only recourse is nation-states using other means of diplomacy and conflict, which may be tangled up in their other interests (e.g., Country A won’t sanction Country B because they are allies). Other frameworks use such bodies successfully, for example the WTO Dispute Settlement Body and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. Unfortunately, disputes taken up by such bodies often take lengthy periods of time to resolve. The average timeframe for a dispute at the WTO is 10 months, at the ICJ it is 4 years, and for the ECJ it is 2 years.34

There is an inherent risk of advanced AI development that breaches the provisions of the treaty, and a risk of disputes relating to treaty provisions which, in extreme cases, could have the potential to spiral into conflict between states. It is therefore necessary to construct a settlement body with legitimacy that can both fairly and correctly adjudicate disputes, and do so in a timely manner for cases that require it.

Mechanism

Implementation and enforcement

The IAT should be established with a comprehensive organizational structure, in order to be able to effectively, correctly, and speedily, adjudicate disputes arising within the AI treaty framework.

At the core of the IAT is the Court, which would consist of 31 judges appointed by IASC Council to serve six-year renewable terms. The Court would make use of a chambers system, modeled off the European Court of Justice, where by default cases are heard by a panel of 5 judges. More significant cases could be heard by a grand chamber of 15. As with the ECJ, chambers could make use of Advocates General to obtain independent legal opinions.

We expect that cases will arise where a delayed judgment could be costly to humanity in terms of risk, and therefore a system is needed to prioritize certain cases and ensure timely processing.

For this reason, we also propose the establishment of a Risk Assessment Panel, to determine which cases must be prioritized, and a Rapid Response Panel, where cases of the highest priority can be referred to.

In addition, the Court should include an appellate body, where cases can be re-examined.

For a more detailed look at the organizational structure of the IAT, see the annexes.

Once a ruling has been issued, parties to the AI Treaty are expected to comply with the decision. If they fail to do so, the IAT must oversee the implementation of the ruling and can authorize the imposition of measures outlined in the AI Treaty framework, such as economic sanctions, similar to existing trade agreements.

43 Of course, any such system should be solely focused on safety-preservation and have appropriate mechanisms to ensure such monitoring could not be used to harm users for their free expression.

44 “WTO Dispute Settlement Body developments in 2010”, WTO, 2011